Beeest: from Plymouth to Public Art

Twisp Commons Park

The project is made possible through a collaboration of Methow Salmon Recovery Foundation and Methow Arts Alliance.

by Ashley Lodato, Methow Arts staff writer

When Barry Stromberger bought a 1951 Plymouth Cranbrook for $25 in college, he never dreamed that one day he would be charged with cutting one into pieces. But fate has a way of intervening in serendipitous ways, and many years later he spent as much time carving up a derelict Cranbrook as he did driving one as a student.

The story of Beeest, the new public art piece installed in the commons outside the Methow Valley Community Center, begins long before Stromberger fired up his angle grinder early in the summer of 2016, and even before he got involved with creating metal art from the bodies of old cars used as riprap along the banks of the Methow River. Beeest was born, says Stromberger— in form if not in name— about a decade ago, through conversations with late valley resident Ernie Chenel.

CLICK HERE for Facebook photos and video.

“Ernie and I used to talk about the flagpole at the Senior Center,” says Stromberger. “It was vandalized and needed a new top. I always thought it should be a yellow jacket up there.” The seed was planted, and although that particular project never came to fruition, Stromberger never lost sight of the image of a giant yellow and black predatory wasp soaring above Twisp, a nod to the ubiquitous pest of Twisp summers, to the mascot of the former Twisp High School, and to the insect whose Native American translation allegedly gave the town of Twisp its name.

You’ll find many references to the wasp in Twisp. “Twisp is allegedly a modification of the Salish word t-wapsp, meaning “yellowjacket,” or twistp, “the sound of a buzzing wasp.”

The opportunity to bring his vision to reality arose in 2015, when Stromberger was awarded a commission to create a public art piece out of the old cars that were being pulled from the river as part of a cleanup effort to improve salmon habitat. Methow Salmon Recovery Foundation, in conjunction with the state Department of Natural Resources, removed about 40 cars—“Detroit riprap”—from the riverbank over the past two years. Three of these—two black cars and a yellow Plymouth—were slated for Stromberger’s project.

The opportunity to bring his vision to reality arose in 2015, when Stromberger was awarded a commission to create a public art piece out of the old cars that were being pulled from the river as part of a cleanup effort to improve salmon habitat. Methow Salmon Recovery Foundation, in conjunction with the state Department of Natural Resources, removed about 40 cars—“Detroit riprap”—from the riverbank over the past two years. Three of these—two black cars and a yellow Plymouth—were slated for Stromberger’s project.

The project was delayed initially by Stromberger’s two knee replacements in the summer of 2015. “When they were pulling the cars out I was just limping around, so I wasn’t able to get down to the river and choose the exact cars I wanted,” says Stromberger. “The best I could do was hobble along the top of the bank and make a big X with spray paint above the cars I thought would work for me.”

When the cars were recovered and delivered to his shop, Stromberger was dismayed at their condition. “By the time they got the rocks and roots out, and cut off the roofs of the cars to pull them out, they were pretty mangled,” he says. “I started having doubts about my ability to pull this off.”

Stromberger admits that at one point he tried to pull out of the project. “I’m a craftsperson,” he says. “I make functional metal pieces. I’m not an artist. I’d never done anything like this before.” But he says he lay awake at night thinking about the project, and downsizing a bit (the original Beeest was to be 12’ long), and figured out how he would build the yellow jacket.

Detailed drawings, cardboard silhouette cutouts, paper patterns, and a long storyboard of yellow jackets helped Stromberger finesse the details and measurements of the design. Still, he says, “I could never be sure I had enough yellow metal.” (He did.)

When it was time to start building, Stromberger first created a 3D armature—another first for him. “Most of my work is gates, grates, and hardware,” he says. “And some 2D commemorative pieces,” he adds, referring to public art such as the Wildland Firefighter Memorial in the Winthrop Park and the McCabe Memorial at Liberty Bell High School. But although Stromberger doesn’t call himself an artist, the aesthetic of his work suggests otherwise. When you see his intricate metal doors or gates with flowers and leaves, or the backrest of a bench under a kiosk at the Mazama Corral, you see the imagination of an artist intertwined with the practicality of a craftsman.

When it was time to start building, Stromberger first created a 3D armature—another first for him. “Most of my work is gates, grates, and hardware,” he says. “And some 2D commemorative pieces,” he adds, referring to public art such as the Wildland Firefighter Memorial in the Winthrop Park and the McCabe Memorial at Liberty Bell High School. But although Stromberger doesn’t call himself an artist, the aesthetic of his work suggests otherwise. When you see his intricate metal doors or gates with flowers and leaves, or the backrest of a bench under a kiosk at the Mazama Corral, you see the imagination of an artist intertwined with the practicality of a craftsman.

Once the armature was created, Stromberger set about the painstaking process of “skinning” the insect—cutting palm-sized pieces of metal from the cars and welding them like shingles to create the yellow jacket’s head and body. Skinning was “excruciatingly slow,” says Stromberger. “ It was pretty much all I did all summer.” Each piece of metal was measured against a corresponding paper pattern, so that Stromberger could ensure that the pieces would fit together properly and create the three rounded pieces of the yellow jacket’s body.

Because heat would burn the original paint off the old cars, and because Stromberger wanted to retain the antique, weathered visual effect of the old paint, Stromberger couldn’t use a plasma cutter or any other tool that would have made the skinning process more efficient. His angle grinder got the job done, but it was laborious, and he wore out at least 100 metal cutoff wheels. “At one point I had to rush order a whole new batch of the wheels,” he says.

The heat of a Methow summer also presented a challenge to Stromberger, who had to construct Beeest outside his studio due to the size of the sculpture. “Some days it was so hot I couldn’t even touch the metal,” he says.

Stromberger pounded the metal skin to create the proper rounding, which was a tiring and deafening process. The angle grinder was loud, too: a thousand angry wasps whining in Stromberger’s ears six hours a day.

Stromberger pounded the metal skin to create the proper rounding, which was a tiring and deafening process. The angle grinder was loud, too: a thousand angry wasps whining in Stromberger’s ears six hours a day.

Finally, the weight of the sculpture eventually posed a problem. Stromberger worked on Beeest while it was suspended, chicken-style, on a rotisserie, so that he could turn it to work on different sections at a comfortable level. “Once it started coming together, though,” he says, “it got so heavy that it was very hard to turn it.”

While constructing Beeest, Stromberger found himself researching topics he never imagined he would. “I spent hours looking into paint,” he says. Stromberger’s original plan involved touching up the welded points with paint to match the original color. But as he got deeper into the paint research, eventually connecting with local car restoration expert Steve Mickens, he learned that the clear-coat lacquer he planned to varnish the yellow jacket with would lift off any new enamel paint. Mickens convinced Stromberger to leave the original paint untouched, with weld lines exposed. The resulting look is deliberately unpolished, and consistent with a real yellow jacket’s banding. Although Stromberger did coat the insect with a UV resistant lacquer to delay the eventual fading of the colors, he notes that over time their vibrancy will diminish.

At one point Stromberger needed to locate a yellow jacket in order to study the way its legs attach to its underbelly. “And I couldn’t find one!” he says (quite possibly the first time ever any Methow resident has actually needed a yellow jacket and been unable to find one).

Still, the sight of the finished sculpture takes some of the sting out of Stromberger’s summer of hot, heavy labor; Beeest pretty closely resembles Stromberger’s original vision. When asked what materials he would have used for Beeest had the project been a straight-up commission not involving old cars, Stromberger replies without hesitation. “New steel,” he says. “And no clear coat. I would have just made it a big rusty bug.”

When Beeest was trucked from the slab in front of Stromberger’s studio to its new home in the Twisp Commons in October it created quite a buzz. Groups of people gathered to watch a crane hoist the yellow jacket onto its lofty perch overlooking the park. Stromberger fixed it in position, removed the lifting chain, and climbed back down the ladder; his contact with the beast that had consumed his summer was over. Beeest now hovers in perpetuity over those going about their daily lives in Twisp, a signature landmark for the town that bears its name.

Sponsored by Methow Salmon Recovery Foundation, WA Department of Natural Resources and the Bureau of Reclamation.

This is a project of Methow Arts Alliance and Methow Salmon Recovery Foundation.

CLICK HERE for Facebook photos and video.

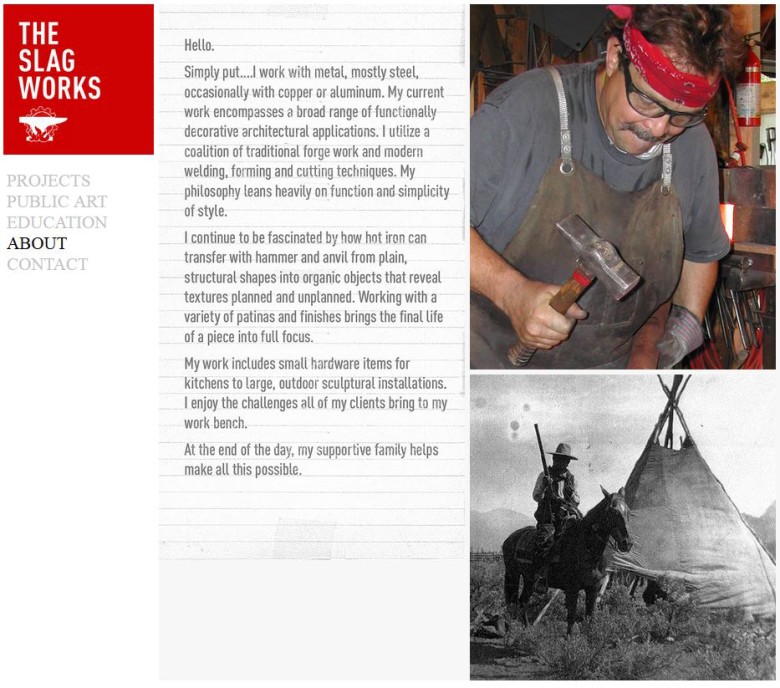

ABOUT BARRY. More information about Barry Stromberger can be found on his website theslagworks.com