By Ryan Bell

Photography by Sol Gutierrez

A radio plays somewhere in the dark interior of Don Ashford’s basement pottery studio, located on the TwispWorks campus in Twisp, Washington. The song is “Just Like That,” an R&B hit from 1960 called by the doo wop group The Robins.

I like Betty, but she’s – too big

And Jenny, she’s – too small

Linda, she’s – too fat

And Marylou – too tall

But you’re just right

So I like you best of all.

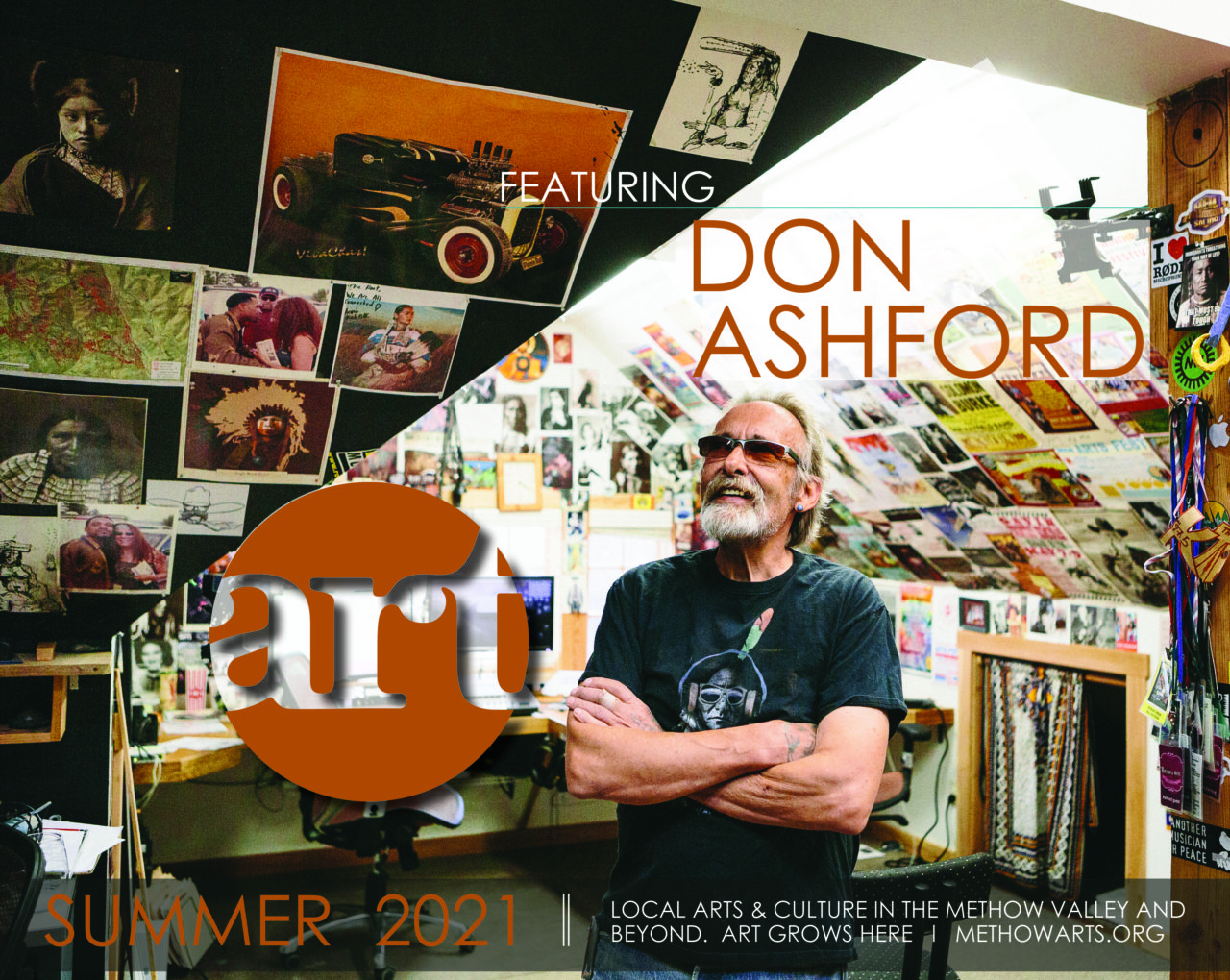

Ashford owns the community radio station 97.5 FM, K-ROOT, and always has a radio playing nearby so he can keep an ear on the airwaves to make sure the station is running smoothly. He launched the station in 1996 and it’s so thoroughly become his identity that only a long-time resident of the Methow Valley would remember that, before K-ROOT, he sold pottery alongside his wife Sara’s artwork at Ashford Gallery for 20 years in Winthrop.

“I think of myself as an artist who happens to own a radio station,” Ashford says. “But the radio needed so much attention that I took a break from pottery 10 years ago. I wanted my investors to know I was giving it my best.”

Two years ago, though, Ashford felt pottery calling. He asked TwispWorks if he could open a pottery studio in the basement of the same building as the radio station. He now spends his days on a journey between the building’s third floor, where he broadcasts music on the airwaves, and the subliminal space of the basement where he makes conceptual mask art as well as functional pottery, such as cups and sauerkraut crocks.

At age 71, Ashford has struck a balance between the two great creative forces of his life: music and pottery. The balance has not been easy to strike.

A mellowed-down instrumental version of “Blue Moon,” by Hank C. Burnette, comes on the radio. I imagine hearing a verse from the 1961 original, by The Marcels.

Snake Farm – It just sounds nasty

Snake Farm – well it pretty much is

Snake Farm – It’s a reptile house

Snake Farm … Ooooohhh

Well Ramona likes her malt liquor

And a band from Wales that’s called The Alarm

She said she cried when they broke up

She still plays their records at the snake farm

I feel the masks looking at me before I can see them hanging on the far end of the studio. One is Medusa-like, with branches coming out of its head instead of snakes. Another has giant eye sockets with copper inlay that give it a facial expression of horrified astonishment. And a third looks like a giant red door knocker with ponytails.

Up close, I see that two of the masks are shaped like raven skulls. Ashford made them in collaboration with his oldest daughter, the jeweler Grace Ashford. They were among 40 artists invited to contribute to the show “In The Company of Crows & Ravens,” held this spring at the Confluence Gallery.

“We started out by asking: What would the ravens say to us?” Ashford says. “I’ve had a couple of instances in my life where I felt like ravens had said something to me. And it was basically: ‘Wake the f*** up! You’re being devoured by consumerism.’’”

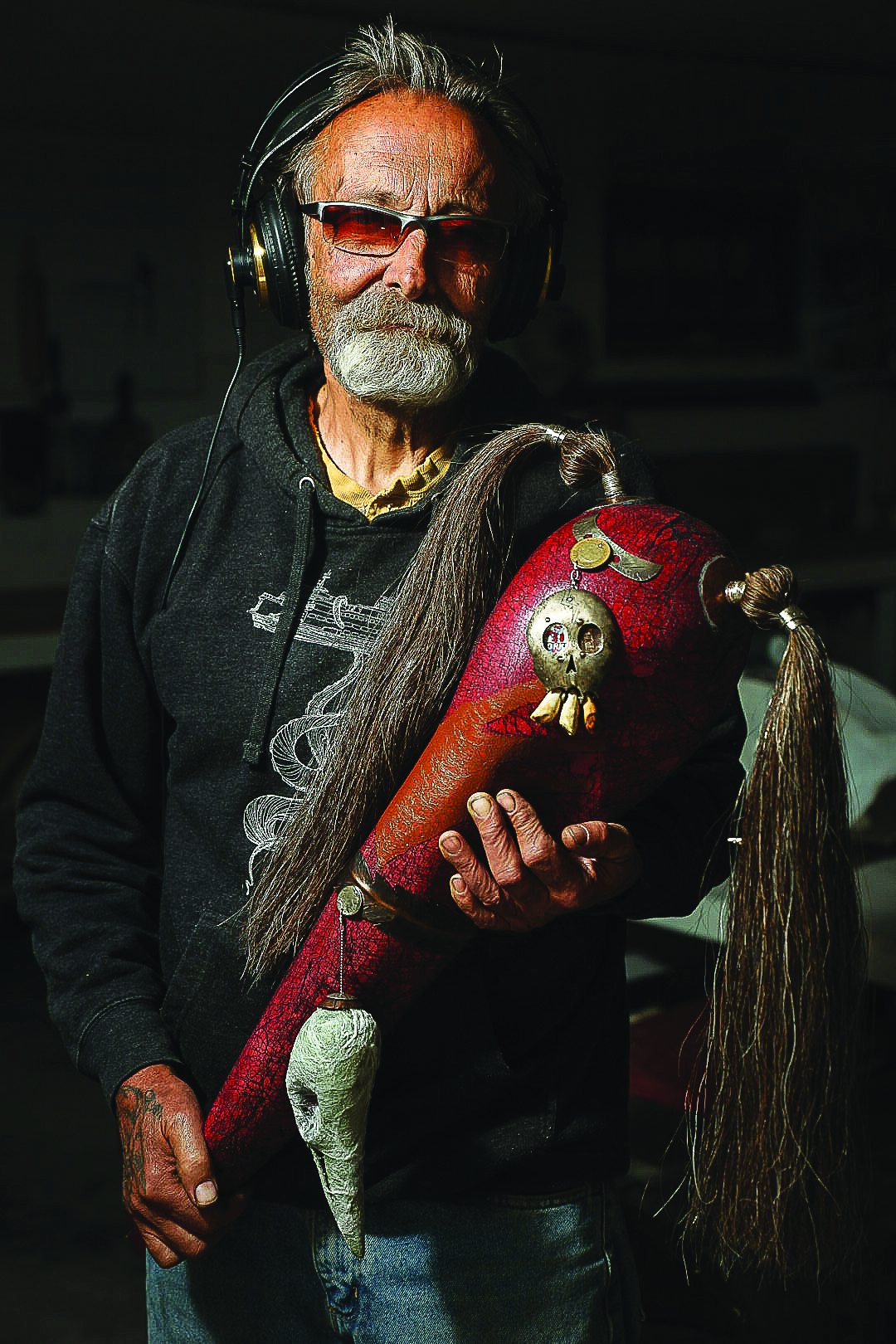

In making the masks, a few themes emerged. The brass-eyed mask, which includes silhouettes of oil derricks that look like ravens atop carion, admonishes us for the damage done by the petro-chemical industry. A second mask, now on display at Sara Ashford’s gallery at TwispWorks, is about the life-giving potential of seeds. The third, the red pony-tailed mask took on a particularly powerful meaning that Ashford didn’t see coming.

“I woke up one morning with the idea of painting a hand print across the mask,” he says, “kind of like you would see on a war pony’s rump. Crows are spiritual for many Native Americans. But then my wife, Sarah, told me that the handprint has become a symbol for disappeared and murdered Native American women.”

Ashford asked fellow artist Betania, owner of Bristle & Stick Handcrafted Brooms, if they would consider collaborating. As a person of Native American descent, Betania was game. By chance, Betania had just mixed a batch of milk paint dyed with earth pigments that they used for the finished product. One final detail is a miniature crow skull made of a translucent material hanging from a chain. “That little gizmo sort of symbolizes the babies that will never be born from these missing women,” he says.

As a new song comes on the radio, we ascend from the pottery studio to the radio station.

“Rockin’ Bones,” by Mad Sin

Well, when I die don’t you bury me at all

Just nail my bones up on the wall

Beneath these bones let these words be seen

This is the bloody gears of a boppin’ machine

Roll on

Rock on

Yeah, raw bones

Well, there’s still a lot of rhythm in these rockin’ bones, ooh.

There are two large bear paws tattooed on the backs of Ashford’s hands. He has turquoise studs in both ears. And he wears a sweatshirt with the drawing of a giant octopus grappling with a ferry boat. (“Let Mother Nature prevail,” he says.)

In other words, Ashford is not someone I would have guessed owns a FitBit. It was a birthday present from his kids who got the device so he could measure his sleep rhythms. Ashford is intensely curious about his state of sleep. He wore the FitBit for a few months, downloaded the data and found – not much.

He sleeps an average of 5 hours and 45 minutes. When he lays down, he goes to sleep almost immediately. He rarely enters a deep state of REM. And when he wakes up, he regains consciousness quickly and gets up from bed right away. Golly, wow.

He quit the FitBit and now just trusts his sleep state for the mysterious force that it is.

“When I lay down, I just think about what’s happening in my life,” he says. “Like, what am I doing in the garden? What am I doing in the pottery shop? If I’m at a confusion point with the radio, I ask for some clarity on what to do. Frequently, I’ll wake up and go, ‘Okay, here’s the solution to that. Cool. I’m doing that.’”

Occasionally, his sleep state will offer up an artistic trinket. Like the morning he woke up with an idea for a mask that would be about, well, the clarifying power of sleep.

“I pictured a mask floating upside down,” he says, “with skeleton keys dangling from springs. I have a collection of rusty skeleton keys, so I dipped them in acid to give them the same color. But in the bunch there was a chrome-plated key with the word ‘Clarion’ stamped on it. The finished mask has all these black keys hanging in space and this one, chrome ‘Clarion’ key hanging in the middle.”

He adds: “This is what I think happens in sleep. I can get my question answered from ‘out there’ – maybe it’s the universe, or maybe it’s my dead son. Who knows.”

“Pretty As You Feel,” by Jefferson Airplane

When you wake up in the morning

Rub some sleep from your eye

Look inside your mirror

Comb your hair

Don’t give no vanity a second thought

No No No

Beauty’s only skin deep

It goes just so far ’cause

You’re only pretty as you feel

As pretty as you feel inside

So, about the bear paw tattoos. Ashford admits there’s a part of him that’s lazy. Sometimes he’d rather sit on the couch all day. He got the bear paws tattooed on his hands so that whenever he looks down, they remind him to keep going. But why bear paws? To honor his deceased son, Dov Bear Ashford.

“When a kid passes away before the parent, you feel like you owe it to them to live and do something special,” Ashford says. “He endured so much pain during the hell of his sickness, but kept a good attitude. When I look at these hands, it reminds me not to give up. Dov keeps being part of the story. This radio station would never have happened without him because he encouraged me to do it.”

At age 9, Dov was diagnosed with leukemia. He spent extended time inside vapor wrapped rooms, went through experimental surgeries, and became so thoroughly the focal point of the family that Ashford has felt the need to reckon with his other four children.

“When one kid takes up all the time, energy, and resources,” he says, “the others become babysitters and caregivers. None of them got the version of the father I had planned to be. I’ve had friends with kids that died and they ask me when I’m going to take down Dov’s altar. I will never take the fucking altar down. I build it bigger and bigger as the years go by.”

A mellowed-down instrumental version of “Blue Moon,” by Hank C. Burnette, comes on the radio. I imagine hearing a verse from the 1961 original, by The Marcels.

Blue moon

You knew just what I was there for

You heard me saying a prayer for

Someone I really could care for.

And then they suddenly appeared before me

The only one my arms will ever hold

I heard somebody whisper, “Please, adore me”

And when I looked, the moon had turned to gold.

I ask if Ashford ever feels Dov’s presence in the airwaves.

“Dov believed that his molecules would stay around,” he says. “He was a brilliant kid. He spent all that time getting chemo treatment just thinking. He figured out how to make this radio station without needing to buy all the expensive equipment. He built the computer framework.”

It makes me wonder if he’s ever made a mask to conjure that face which is no longer here.

“At my age, I think a lot about legacy. Fired pottery stays around for a long time. I want these masks to say something satisfying for me and a little beyond that, too. I think death is the next logical progression.”

He adds: “I’ve got a thing downstairs that’s pointing me that way, but it’s kinda painful still,” he says. “It’s a mesh mask they put over Dov’s face when they were radiating his head. It’s a weird, creepy thing that has a lot of bad feelings that I haven’t quite dealt with. That mask is still in front of me.”

The song “Nina Simone,” by Tom Russell, plays on the radio.

I’ve heard the ravens call morning up,

With their little raw saxophones,

But the darkest of ravens,

was Nina Simone.

Yeah we’ve all been to hell and come back

Where love cut us right down to the bone

But walking besides us

Was Nina Simone.