By Marcy Stamper

By Marcy Stamper

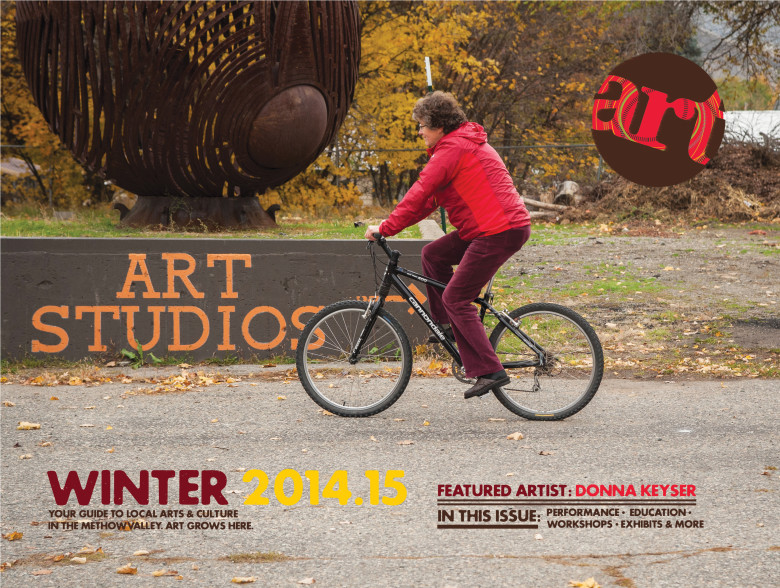

Photos by Teri Pieper

Donna Keyser has had more interesting and idiosyncratic jobs than most people—creating window displays for department stores, designing museum exhibits, pruning apple trees, building architectural models, painting murals, and creating puppets for a theater troupe. With such a long career in art, it is perhaps ironic that it took an accident on a fishing boat in Alaska to spur her to focus on her own painting.

Just three days into the job, Keyser fell off the boat and broke her wrist. It required several surgeries for it to heal properly. She had just rented a new apartment in Seattle but, because of her broken wrist, she couldn’t move her stuff in. “I was disoriented,” she said. “I couldn’t do my design work on the computer or do physical labor.”

Instead, she covered the walls of the empty apartment with long strips of brown Kraft paper and started drawing with color markers, filling the sheets with images of trees.

“I had a list of every emotional experience I ever had with a tree, starting with lying on the ground looking up,” she said. She set out to depict each one.

She remembered the shock of finding that a beloved poplar tree had been cut down. Flipping through drawings from the tree series, she stops at an intense close-up of leaves. “That was a memory of being in that tree when I was 5. The leaves are that big because I was small. There were also bugs and a praying mantis.”

The project launched many more art projects, but Keyser has never stopped focusing on trees. Most of the tree paintings share similar dimensions, but they all originate from different perspectives. There are angular Ponderosa pines, feathery larch, and voluptuously foliated poplars. Some offer a vertiginous view of the trunk, the branches silhouetted against the sky. Others are about the rippling pattern of bark or the spaces between trees. Some are really about sky, with just a hint of the needles protruding into the clouds. The paintings all have an element of abstraction, an examination of shapes and of intense and vibrant colors.

While trees remain a constant source of inspiration, Keyser’s subjects are wide-ranging. “It’s some phenomenal thing that happens in nature. It could even be man-made—it just has to be strong enough for me that I want to start painting it,” she said. That can include old houses, barns, and powerlines, or lakes, wheat fields, and expanses of sky. “I like that place where humans and nature interact,” she said.

While trees remain a constant source of inspiration, Keyser’s subjects are wide-ranging. “It’s some phenomenal thing that happens in nature. It could even be man-made—it just has to be strong enough for me that I want to start painting it,” she said. That can include old houses, barns, and powerlines, or lakes, wheat fields, and expanses of sky. “I like that place where humans and nature interact,” she said.

Keyser often uses photography to capture her perception of nature. “Once you start looking, all of a sudden, the world becomes something different,” she said. “I like what happens when a camera finds something other than what you see—like taking a long exposure at night.”

While taking photos may help her see things in a new way, painting—usually in acrylic on wooden panels—invites another appreciation altogether.

“The act of painting something makes it unreal, instead of being a photograph,” she said.

“These things can take you somewhere—it’s always as if the whole world turns itself inside out,” she said. “The sky pulls me outside and starts the process of looking at things—and then it gets really interesting.”

The walls of Keyser’s studio are lined with vertical paintings, most several times taller than they are wide. The dimensions suit Keyser. “I like them because they’re my size,” she said. “It’s very, very simple. They’re friends of mine—long, skinny people,” she said.

The walls of Keyser’s studio are lined with vertical paintings, most several times taller than they are wide. The dimensions suit Keyser. “I like them because they’re my size,” she said. “It’s very, very simple. They’re friends of mine—long, skinny people,” she said.

The format lends itself to trees, but Keyser also likes what it does for her art and the process of creating it. “It forces you to make an interesting composition,” she said.

It also allows her to experience the physicality of painting. She paints the top of a canvas standing up, then turns it upside-down or sideways to work on another section. “If I had the ability, I would be making paintings wall-size, or building-size, or parking-lot size,” she said. “I like painting with my whole body.”

She also switches the paintbrush from her right to left hand to tap into each side of the brain and engage different muscles. She may set up 11 panels in a row, paint the five on the left with her left hand, the five on her right with her right hand, and then divide the center panel down the middle.

Painting multiple panels also changes the aesthetic impact. “The composition starts to be the whole thing,” she said. “They all actually work together—you can change them any way and they say something different.”

Keyser’s early tree series built on a lifelong attraction to ambitious projects and numbers—big numbers. When she was living in Seattle, she lost many friends to AIDS, and began work on a project that would honor them. She painted ordinary wooden clothespins and inscribed fortunes and a phone number on each one. She turned out 1,000 clothespins, each with a unique message or design. “I gave them to everyone I could think of, and left them in a box on Broadway for people to take,” she said.

As she thought deeply about someone she loved and had lost, the clothespins would come to reflect that person’s qualities. “It was sort of like a really long poem—a meditation about everything I saw that person do.”

The phone number on the clothespins reached an answering machine where Keyser recorded a new poem or message every day. Many of the callers left messages as part of the anonymous exchange.

She also created 1,000 matchbook collages. “Making 1,000 of something is painful,” she conceded. “It was a time when I was obsessed with numbers, too.”

The clothespin project was also a response to the anonymity of urban life after her first stint in the Methow Valley, living on McFarland Creek near the town of Methow in the 1980s.

On McFarland Creek, Keyser lived without heat, electricity, or phone. If people wanted to talk to you, they would just stop by, she said, and help weed the garden while they visited. By contrast, going to art school in Seattle immersed her in a world of almost overwhelming abundance, where people scheduled appointments two weeks in advance.

Although the town of Methow was hardly a center of art in the 1980s, Keyser has always been willing to take risks. She rented a space in town and turned it into a studio and gallery.

“I just set up experiments,” she said. “I was tired of the drudgery of manual labor and decided I was going to be an artist. Every morning I went to my studio and made really bad art,” she said. “I’m not afraid of making things, or of failure or trying something new.”

Keyser returned to the Methow about five years ago and continued her eclectic involvement in art. She managed the gallery and gift shop at Confluence Gallery, continued to paint and create her own art, and launched several exhibit spaces and a business doing commercial and sign design.

Today she and a partner curate three galleries: the Methow Gallery at TwispWorks, The Gallery at Sun Mountain Lodge, and an exhibition space at the Merc Playhouse in Twisp.

They will continue to operate those galleries, but is moving her design and sign business to the Glover Street storefront formerly occupied by the Peligro jewelry studio and gallery.

“That space is beautiful and elegant,” she said. “I couldn’t stand the thought of it being empty.” In addition to having a base for her sign business, she plans to exhibit art and functional and decorative objects for the home.

She is also brainstorming, currently designing a series of tables with an illuminated shelf for growing edible sprouts and micro-greens. “I have a brilliant team of experts here, who work in metal and wood, to collaborate with,” she said. “I’m into serving the community of artists, because it’s been really rich and fruitful for me.”

She also trusts her fundamental approach to art. “It has to have the emotional experience, although not necessarily be highly charged. It just has to be beautiful.”

Find out more about Donna here on her artist page: CLICK HERE.

- Download the WINTER ART Magazine

- Sign Up for our newsletter.