By Marcy Stamper, Photos by E.A. Weymuller

By Marcy Stamper, Photos by E.A. Weymuller

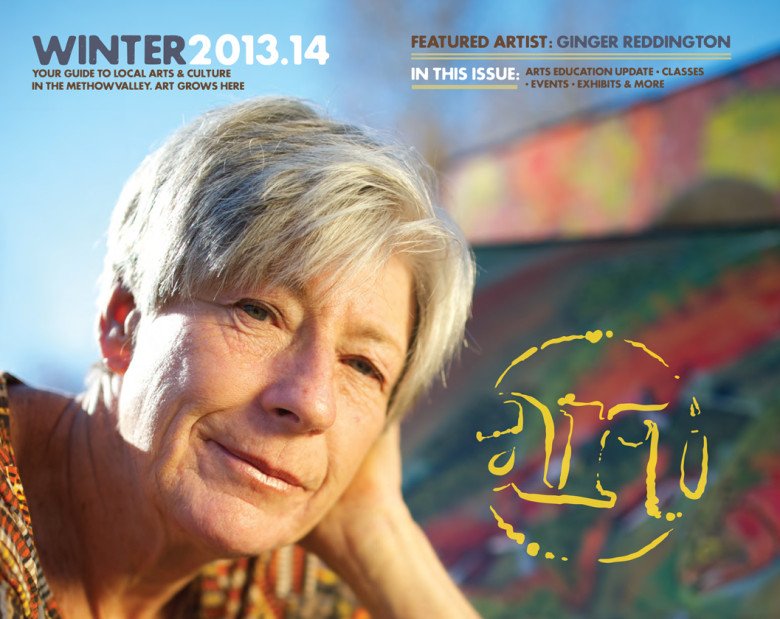

The people, animals—and even trees—in Ginger Reddington’s paintings pulse with such vitality that they often extend beyond the frame, as if propelled by so much speed or energy that they can’t be contained.

“They’re not confined,” said Reddington. And neither is she. She bought her first horse when she was a girl and would stay out all day riding him, covering hundreds of miles in the then-unpopulated area near Tacoma. She has since packed into much of the high country in the North Cascades.

This passion for exploring is central to Reddington’s creative process as an artist. “I have to experience stuff to paint,” she said. If the sun hits the hills in a certain way, she may take a photo as a reference, but it is the feeling of being on her horse or in the mountains that she wants to convey through her art. “I’ve seen things most people don’t get to see, gone places most people don’t get to go, and had adventures most people don’t get to have,” she said.

Even her approach to painting—generally thought of as one of the more sedentary art forms—is quite physical, involving vigorous scraping of wax as part of a multi-step process.

Reddington started her life in art at age six, bicycling to and from oil-painting lessons. But between working as an art instructor, running a business raising and breeding show horses, and raising a family, she had to fit in her painting when she could.

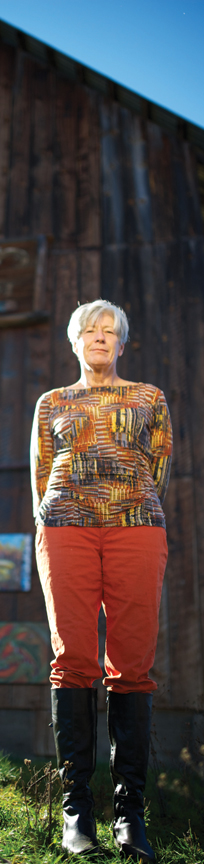

When the Reddingtons moved to the Methow nine years ago, she was able to channel more of that energy into her art. Ginger’s husband, Don, whom she calls her greatest supporter, presented her with a shed he had converted to a studio. “I told her to go for it as an artist,” said Don. He also urged her to experiment with a new style.

greatest supporter, presented her with a shed he had converted to a studio. “I told her to go for it as an artist,” said Don. He also urged her to experiment with a new style.

“I was doing classic watercolor and realism, as I’d been taught,” said Ginger. Although back in high school she had dabbled in abstract paintings with exaggerated, surreal colors, she painted representational landscapes for most of her career. “But Don is pretty intuitive,” she said.

It took her six months to arrive at a new aesthetic and to perfect the technique to achieve it, which expands on a popular lesson she did with her young students. They would draw in oil pastels, outline the image with a ribbon of glue, and then cover the whole thing with a solution of black India ink and dish soap. When it all dried, the kids would scratch between the three-dimensional glue lines to reveal their picture. “They absolutely loved it,” said Reddington.

Reddington has refined the technique, incorporating layers of watercolors and acrylics, raised contours, and two applications of wax. The seven-step process gives her work a sense of depth and character and the wax provides sheen and protection.

It’s also a somewhat unusual approach to creating visual art, since the entire image gets covered up during the process. “During the last stage—after I get it all sealed—you can’t see it anymore till I scrape it,” said Reddington.

As she worked to depict her experiences, Reddington’s style became looser, drawing on her affinity for abstraction and fields of bright color and favoring the tight framing that gives her subjects that distinctive energy. “It’s realism, but it’s not,” she said. “It’s basically blobs of color, but it works.”

She also uses shapes that convey fluidity and movement. One recurring motif is the circle, both as a symbol and as a compositional device. In one painting, a circle of foals essentially creates its own frame. Her paintings of fish often show them cycling as if caught in an eddy. “Circles are really important,” said Reddington. “They reflect the circle of life—and the nature of relationships.”

Reddington paints some subjects from a wider vantage point. Paintings of a high-mountain ridge before a storm, a field of haystacks, and the Seattle skyline (a rare urban subject for her) are all pulled back far enough to highlight the drama of the sky.

While most of Reddington’s paintings are of nature and wildlife, and people like climbers and mountain bikers in those environments, she still enjoys painting the rusted cars and trucks that have become a part of the landscape themselves.

While most of Reddington’s paintings are of nature and wildlife, and people like climbers and mountain bikers in those environments, she still enjoys painting the rusted cars and trucks that have become a part of the landscape themselves.

Reddington’s distinctive style has resonated with collectors and galleries—these days, she averages about one sale a week, and last year sold 59 paintings. She points to one yardstick of her success—she and Don have a weekly dinner date, and Ginger treats when she has sold a painting. It’s been five years since Don has bought his own dinner.

Reddington believes in making art affordable. “I want my paintings available not just for people with extra money who are collectors, but for people who like the Methow and for young people just getting into art,” she said. Many of her clients have visited the valley or found her through her website. “There are not many states I don’t have a painting in,” she said.

Reddington also gets numerous commissions. “I involve the people from day one,” she said. She sends photos of every stage, from the initial sketch through the layering process, so that her clients can participate. “They love being a part of it—they’ve created a child. And it’s fun for me to be part of it, trying to capture their heart and put it on canvas,” she said.

Devoting time to her painting is “the gift of retirement,” she said. “I’m having so much fun that I don’t realize it’s turned into a business. As a person who was happy being a recluse and doing things with my husband, I’ve met amazing friends as clients.”

Reddington recalls a lesson in keeping art vital from the time she spent as an artist-in-residence in a juvenile-detention facility. Despite the presence of armed guards, the young residents flourished when given the opportunity to express themselves creatively. “Their days were so structured, but in art class, they could just let their minds flow and come in and enjoy it. Doing it was as much fun as the product—that was really important,” she said.

Despite a series of back surgeries for a condition that could have left her paralyzed, Reddington is still out mountain climbing, skiing, and mountain biking in the woods near her home. One of the few things she’s had to give up since the surgery is snowboarding, which she did for the first time to celebrate her 60th birthday.

“I’m supposed to be more cautious,” she said, “but when you’re given more time, you’ve got to use it to the fullest.”

In addition to special exhibits in the Methow, Wenatchee and Leavenworth, Reddington’s art is typically on view at several venues in the area. She has a regular, changing exhibit at the Twisp River Pub, and often shows at the Methow Valley Inn, Twisp River Suites and the Country Clinic in Winthrop. She is exhibiting at the Lost River Winery tasting room in Seattle through the end of March. She’ll have shows at the Cinnamon Twisp and Rocking Horse bakeries next year.

(Photos by E.A. Weymuller)

- Download the 2013.14 Winter ART Magazine (PDF)

- Sign Up for our newsletter.