WINTER ART MAGAZINE: click here for PDF.

Thank you to our magazine supporters: Icicle Fund, ArtsWA, Sun Mountain Lodge, PSFA, Okanogan County Hotel/Motel Lodging Tax Fund, Blue Star Coffee Roasters, many businesses and generous donors.

By Ryan Bell. Photographs by Sol Gutierrez.

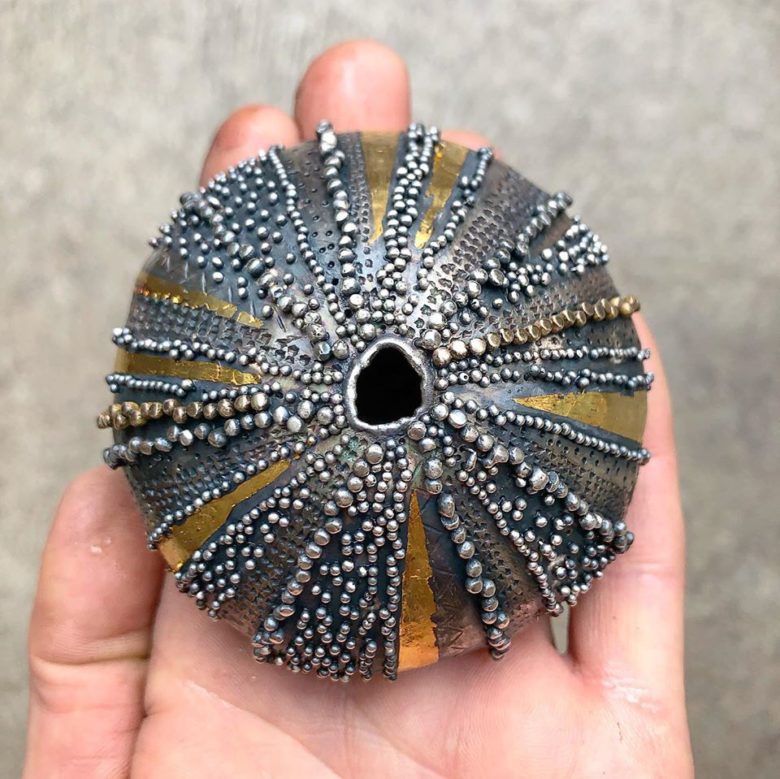

The “creative spark” is a mysterious force. It can occur at any moment, ignited by the unlikeliest of sources. For silversmith Nicole Ringgold, she’s found it in a barnacle-encrusted seashell discovered while beachcombing on the Puget Sound. In the hexagonal honeycomb of the honeybee hives her husband keeps at their home in Winthrop, Washington. In a glass shard tumbled smooth by the Pacific Ocean and deposited on the beaches of Baja Mexico.

The “creative spark” is a mysterious force. It can occur at any moment, ignited by the unlikeliest of sources. For silversmith Nicole Ringgold, she’s found it in a barnacle-encrusted seashell discovered while beachcombing on the Puget Sound. In the hexagonal honeycomb of the honeybee hives her husband keeps at their home in Winthrop, Washington. In a glass shard tumbled smooth by the Pacific Ocean and deposited on the beaches of Baja Mexico.

Studying them as source material, she crafts true-to-life replicas as bracelets, rings, necklaces, and other pieces of “botanic jewelry.” Her work has been commissioned by collectors from around the world, and has earned her 108,000 followers on Instagram, and counting.

Studying them as source material, she crafts true-to-life replicas as bracelets, rings, necklaces, and other pieces of “botanic jewelry.” Her work has been commissioned by collectors from around the world, and has earned her 108,000 followers on Instagram, and counting.

Yet, Ringgold’s most powerful creative spark came in a form that was both literal and symbolic. On the afternoon of August 1, 2014, a trailer traveling down Highway 20 had a blown-out tire. The rim scraped across the asphalt, sending sparks that caught fire in dry grass along the roadside. Within a few hours, the Rising Eagle Road Fire burned 579 acres and destroyed 22 structures, including Ringgold’s home.

The fire consumed everything. The small art studio where Ringgold had been learning to make wire-wrapped and stone-beveled jewelry. The kitchen cabinets whose doorknobs and drawer pulls she’d crafted out of river rock and wine corks. The fire had burned so hotly that her drill press was melted into a metallic glob.

At that time, few people knew that Ringgold dabbled in metalsmithing. She was best known as the director of Confluence Gallery and Art Center in Twisp, and before that as director of Little Star Montessori School in Winthrop. Art had always been secondary to what she saw as her professional career in social work. Paradoxically, by burning down Ringgold’s home, the fire had opened a career door. (Photo by Ryan Bell.)

At that time, few people knew that Ringgold dabbled in metalsmithing. She was best known as the director of Confluence Gallery and Art Center in Twisp, and before that as director of Little Star Montessori School in Winthrop. Art had always been secondary to what she saw as her professional career in social work. Paradoxically, by burning down Ringgold’s home, the fire had opened a career door. (Photo by Ryan Bell.)

“When you’re in a situation like that, you have a chance to be reborn,” Ringgold says. “My husband knew that I’d always had a dream of dedicating myself to art. We decided to shrink our lifestyle so I could quit my job and commit to becoming an artist.”

She received a grant from the Craft Emergency Relief Fund, an organization helping artists affected by disasters, to buy new silversmithing equipment. And instead of building an in-home studio, Ringgold asked Tess Hoke, owner of the garden supply store Yard Food in Twisp, to rent studio space inside the store’s greenhouse.

There, Ringgold immersed into the world of silversmithing, forging a new professional identity with her blow torch. But it didn’t come easy. At first, Ringgold was stumped for how to establish herself in what seemed like a crowded field of silversmiths incorporating rocks and plants into their jewelry. (Photo by Ryan Bell.)

There, Ringgold immersed into the world of silversmithing, forging a new professional identity with her blow torch. But it didn’t come easy. At first, Ringgold was stumped for how to establish herself in what seemed like a crowded field of silversmiths incorporating rocks and plants into their jewelry. (Photo by Ryan Bell.)

“I needed to figure out how to get ahead,” Ringgold says. “One day, I was out on a trail run when it dawned on me: all those other artists were doing the same thing, making castings of plants and rocks. Nobody was hand-fabricating them from scratch.”

“I needed to figure out how to get ahead,” Ringgold says. “One day, I was out on a trail run when it dawned on me: all those other artists were doing the same thing, making castings of plants and rocks. Nobody was hand-fabricating them from scratch.”

Ringgold believes in the practice of “self challenges” for learning new skills. To become adept at hand-fabricating botanicals, she assigned herself the challenge of collecting 30 unique botanicals and figuring out how to recreate them in silver. She dissected columbine flowers to understand how the petals interwove and connected to the stem. She split open the pearl-shaped leaves of succulent plants to understand their interior so she could create similar structures in silver.

Piece by piece, her studio became like a metallurgic compendium to the natural world. The shelves of her studio look like a botanist’s version of a mad scientist’s laboratory. A paper wasp’s nest on one shelf. Rows of Mason jars filled with colorful rocks. A glass display case of curios gathered on her trips around the world. And on the top shelf of a rolling cart, her most recent haul: a collection of shells and sea glass gathered on a recent trip to Todos Santos, on the Baja Peninsula of Mexico where her family has a vacation home.

Piece by piece, her studio became like a metallurgic compendium to the natural world. The shelves of her studio look like a botanist’s version of a mad scientist’s laboratory. A paper wasp’s nest on one shelf. Rows of Mason jars filled with colorful rocks. A glass display case of curios gathered on her trips around the world. And on the top shelf of a rolling cart, her most recent haul: a collection of shells and sea glass gathered on a recent trip to Todos Santos, on the Baja Peninsula of Mexico where her family has a vacation home.

Customers shopping for garden supplies at Yard Food travel between the two worlds – organic and silver – as they walk the length of the greenhouse. The green-hued building has even become something of a pilgrimage site for silversmiths from around the world who come to Twisp to attend the silversmithing workshops Ringgold periodically will teach.

Customers shopping for garden supplies at Yard Food travel between the two worlds – organic and silver – as they walk the length of the greenhouse. The green-hued building has even become something of a pilgrimage site for silversmiths from around the world who come to Twisp to attend the silversmithing workshops Ringgold periodically will teach.

“I’m told by my students is that, at silversmithing schools, you’re always told you can do it this way, but you can’t do it that way,” Ringgold says. “Apparently, I’ve taken all of the rules and thrown them out the window.”

“I’m told by my students is that, at silversmithing schools, you’re always told you can do it this way, but you can’t do it that way,” Ringgold says. “Apparently, I’ve taken all of the rules and thrown them out the window.”

The first lesson she teaches them – the proper use of a gas torch – is symbolic of the lesson she’s learned from life.

“You have learn to understand this intimidating fire,” Ringgold says. “Most people turn their torches up and the heat is too much. That will burn the metal. But if you adjust the gas’s mixture of oxygen just right, you get this narrow blue cone of heat that is just right.”

In other words, by harnessing the power of flame, Ringgold has discovered her life’s art.

WINTER ART MAGAZINE: click here for PDF.

Photographs were taken by Sol Gutierrez.

Photographs were taken by Sol Gutierrez.