In the Process

In the Process

By Marcy Stamper

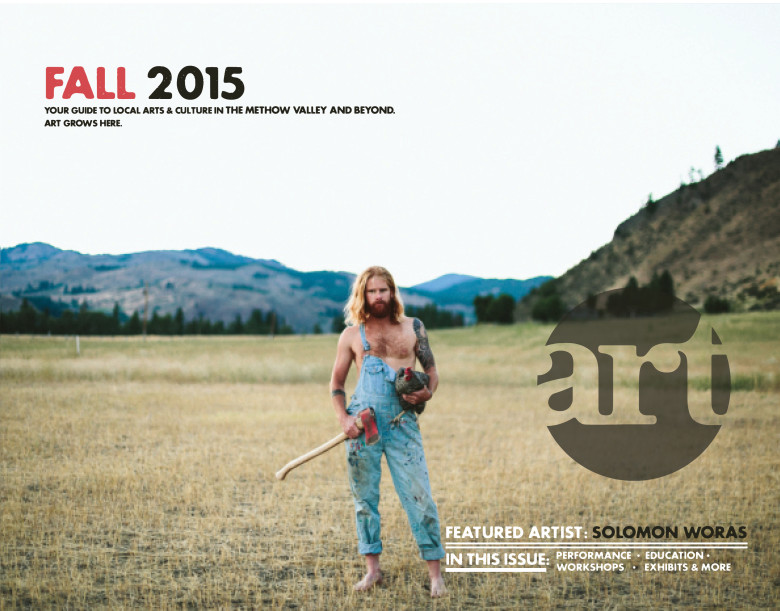

Photos by Sol Gutierrez

READ THE FULL FALL ART MAGAZINE HERE

“Music is one of the most-fun art forms because it’s so collaborative,” said Solomon Woras. “You can’t be as attached to the outcome—you’re forced to let go of it.”

Woras, the lead songwriter and vocalist for the Winthrop-based Americana band Wild Mountain Nation, has been involved in music on and off for his whole life. But he didn’t start writing and singing seriously until about three years ago, when he turned to music during the break-up of his marriage.

At first music was mainly an emotional release but, as his songs became less introspective, Woras gathered a group of musicians to take his ideas further. That led to the formation of the band, appearances at local pubs, and a start on a first album.

Still, he’s a little sheepish about how he got there. “It’s the oldest story in the book,” he said. “How many people have started a country band after the break-up of a relationship?”

While it may have been born out of grief, his music is one of Woras’ greatest joys. “I get charged every time I pick up the guitar,” he said.

While it may have been born out of grief, his music is one of Woras’ greatest joys. “I get charged every time I pick up the guitar,” he said.

Woras even likes the ephemeral nature of music and the fact that a lot of what they do—while jamming, in rehearsal, at a gig—is not documented. “It’s a cathartic release, kind of like a sand painting,” he said. “You just had an almost religious experience—and it’s completely gone.”

By contrast, when Woras reflects on visual art he has done over the years, he can’t quite muster the same detachment. “It’s very rare you would take a painting and hand it to four other people—and then get it back,” he said. “It’s harder not to be selfish with painting. You don’t want people to tinker with it.”

“It’s a nice life lesson in general—to let go of the serious outcome for any situation,” he said.

Although Woras writes most of the songs for Wild Mountain Nation, he said his compositions are really just a starting point, a structure for the others to embellish.

“Ninety-five percent of the enjoyment is to take something you’ve created and get input from other people. It comes back at you as something entirely different,” he said.

The audience’s response also adds to the music. In fact, Woras said he’s less concerned about whether people actually like his music than if they’re genuinely reacting to it. Even someone who criticizes the music has had some kind of experience with it, he said.

Whether it’s music, sculpture, or painting, Woras looks to art to tell stories, often deeply emotional ones. Many of his songs have a dark side. “It appeals to me to have jubilant music with troubling stories,” he said.

He’s written about the break-up of his marriage and last summer’s wildfires. After the fire, he wrote a song from the perspective of an ancient tree that had witnessed the burning of forests and homesteads over the years.

Woras grew up in an artistic family. His father, Phil Woras, is a woodworker and a musician and his mother, Deirdre Cassidy, is an art teacher and a natural singer.

Although Woras always liked music, most of his artistic endeavors have been visual. When he was a kid, he loved sculpture and created his own toys. “I’d make a whole army out of clay—and then destroy it,” he said.

He studied claymation for a while in college and made a few animated films. “It was more about the story and creating a world,” he said. Music proved to be an even better outlet. “With music you can do that so efficiently—it’s like a mini-novel, except you don’t have all the details or the grammar.”

After claymation he migrated to oil painting. His paintings—of trees, of people and musical instruments and dancing frogs—are reminiscent of impressionism, but with more-well-defined lines and forms.

But painting left him longing for the hands-on qualities of clay. Woodworking provided that tactile experience. “You’re always touching wood, feeling it, even though you use tools—it’s sort of like clay in that way,” he said. Five years ago, he joined his father in making cabinets and furniture in Woras Woodworking.

Another appealing aspect of woodworking is that it combines beauty with function. “I struggle with the idea that a painting just hangs on the wall but you don’t use it,” said Woras.

Another appealing aspect of woodworking is that it combines beauty with function. “I struggle with the idea that a painting just hangs on the wall but you don’t use it,” said Woras.

But the functional demands of woodworking can create their own dilemma. Woras admitted that it’s possible to get so focused on the aesthetics that you could make a chair that, while beautiful, is so uncomfortable that no one would sit in it. Worse yet, someone would sit in it and the whole thing would fall apart.

Beyond that, you don’t see the final product until all the joinery is done. “That can be frustrating for somebody who’s really impatient, like me,” Woras said. Compared to clay, wood can be nerve-wracking and unforgiving. “The stakes are so high—you can’t grow wood back.”

He praised his father for his teaching, his patience, and his willingness to work together. “My dad is really gracious. He likes to collaborate and is always open to ideas.”

Woras has designed and crafted some of his own furniture, which he said tends towards the whimsical. He makes extensive use of a sander to create unusually sculptural forms. Subtle bumps protrude from his table legs, the drawers have curving edges, and there are a lot of convex shapes. As a result, some pieces of furniture end up looking like they’ve grown hooves, he said.

For several years, Woras set his art aside—in fact, he set just about everything aside—as he traveled around the country as a bicycle racer.

“It was a job,” he said. “It was a huge part of my life—I always felt I needed to train.” And it was all-encompassing—it ruled what he ate and drank, and his days alternated between tremendous physical exertion and utter exhaustion.

“It was a job,” he said. “It was a huge part of my life—I always felt I needed to train.” And it was all-encompassing—it ruled what he ate and drank, and his days alternated between tremendous physical exertion and utter exhaustion.

He ultimately left racing, wanting to feed his creative side again. Nevertheless, Woras considers himself more of a craftsperson than an artist. “I wouldn’t say I’m an artist, but that’s a part of me I need to engage with to be fully happy,” he said.

He has toyed with writing and illustrating children’s books, wanting to create stories that people can embellish through their own imagination.

“I am drawn to creating an image that’s the tip of the iceberg, just creating in your own mind what’s happening,” he said.

He regularly takes stock of his evolution. “I feel like I’m still in such an embryonic, frustrating stage. But I really like the process of crafting,” he said. “The product itself—whether it’s a song, furniture, or a painting—is not as satisfying.”

Woras acknowledges that his sprawling interests—and sharing custody of his two daughters—have made it hard to focus. “As a creative person, I’m kind of failing at having time to do woodworking or metal,” he said. (He’s interested in creating specialized woodworking tools.)

Still, the areas often overlap. Songs come to him while he’s working in the woodshop or when he’s with his daughters. At ages 4 and 6, they already know all the words to his songs, he said.

Sometimes Woras asks himself about his choices. “Will you make money from art? That’s a funny question,” he said. “It prioritizes the wrong thing—for me, it’s about the process—the goal is to keep doing it.”

“If I can inspire somebody to create something based on that spark—that would be the ultimate situation,” he said.

Look for Solomon Woras’ band Wild Mountain Nation in venues this fall. You can find them on Facebook HERE.

DOWNLOAD THE FULL FALL ART MAGAZINE PDF – HERE

Sign Up for our newsletter.